Illinois school district consolidation provides path to efficiency, lower tax burdens

By Ted Dabrowski, John Klingner

Download Report

Illinois school district consolidation provides path to efficiency, lower tax burdens

By Ted Dabrowski, John Klingner

Download Report

Executive Summary

Illinois has the most units of local government of any state in the country. Many of its nearly 7,000 units of local government are overlapping, duplicative and contribute to Illinois’ growing debt, waste and corruption. These local units of government are also responsible for Illinois’ growing property taxes, which already rank as the third-highest in the country. Many of the state’s local governments could be consolidated – which would help to reduce their negative effects.

Among the key candidates for consolidation are the state’s 859 local school districts, which consume nearly two-thirds of the $27 billion in local property taxes that local governments across Illinois collect each year. Illinois has the fifth-largest number of school districts in the nation.

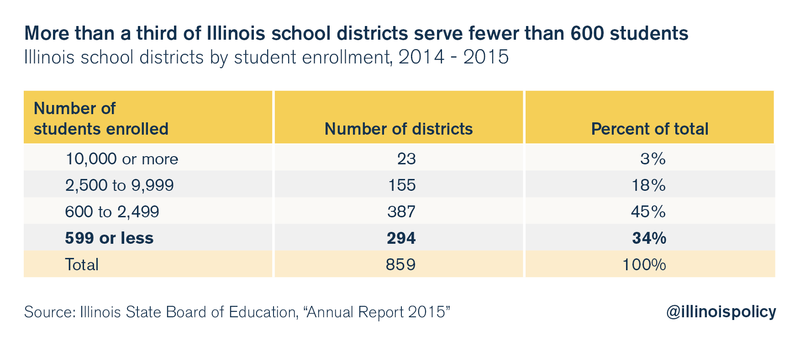

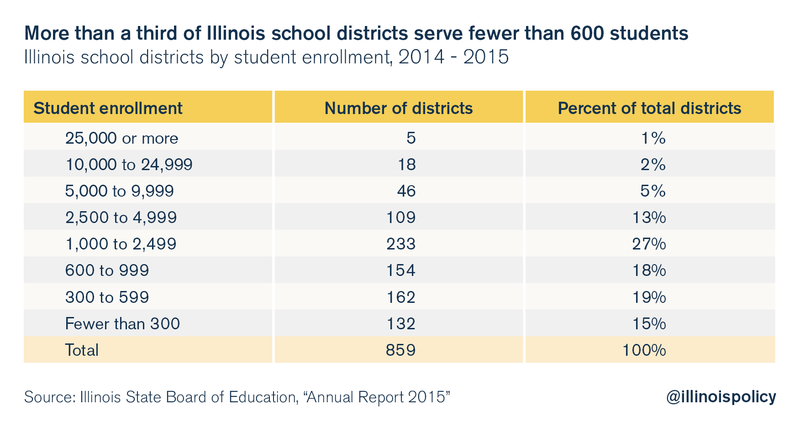

Nearly 25 percent of Illinois school districts serve just one school, and over one-third of all school districts have fewer than 600 students. An additional layer of administration for these districts is inefficient.

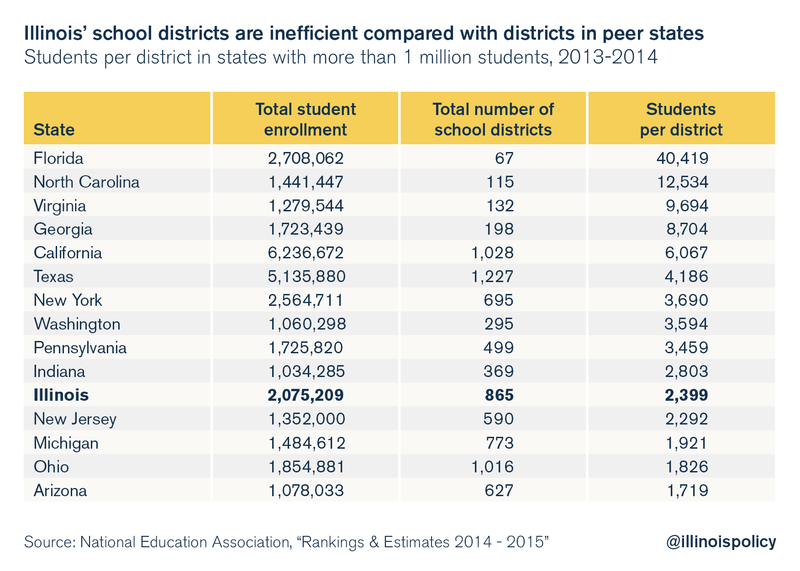

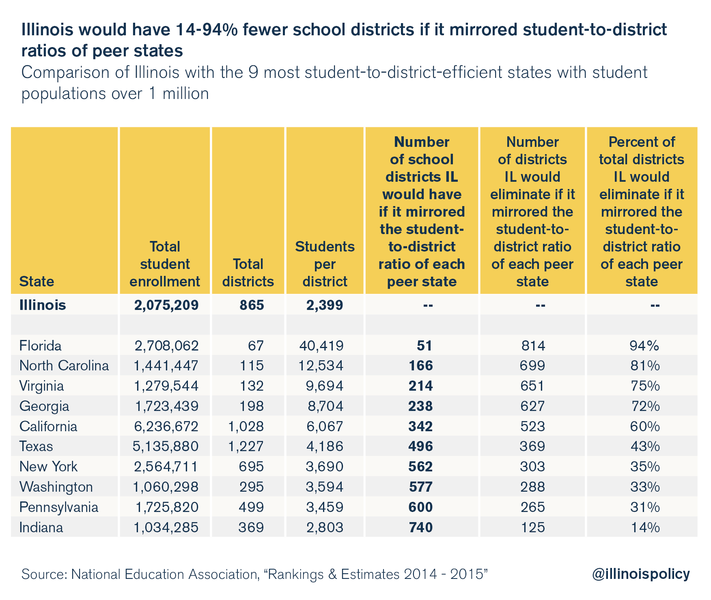

On average, Illinois school districts serve just 2,399 students per district, the fifth-lowest among states with school populations over 1 million. Conversely, California school districts average 6,067 students. If Illinois school districts served the same number of students as California, Illinois would have 500 fewer school districts than it has today.

By cutting the number of school districts in half, Illinois could experience district operating savings of nearly $130 million to $170 million annually and could conservatively save the state $3 billion to $4 billion in pension costs over the next 30 years.

A majority of those savings would be realized by a reduction in district staff. Not only do taxpayers fund the principals, administrators, teachers and buildings at the school level, but they also pay for an additional – and often duplicative – layer of administration at the school district level.

The cost of administrative staffs at school districts adds up quickly. Nearly all districts have superintendents and secretaries, as well as additional personnel in human resources, special education, facilities management, business management and technology. Many districts retain at least one assistant superintendent as well.

Administrative salaries in school districts end up consuming a significant portion of public funding. More than three-quarters of Illinois’ superintendents have six-figure salaries, and many also get additional benefits in car and housing allowances, as well as bonuses. In addition, their high salaries lead to pension benefits of $2 million to $6 million each over the course of their retirements.

For an example of districts where consolidation makes sense, consider New Trier Township High School District 203 and its six elementary feeder districts. Combining these seven districts into one would eliminate many of the 136 administrators directly employed at the seven district offices, saving local taxpayers over $12 million a year in salaries alone, or over $1,000 per student.

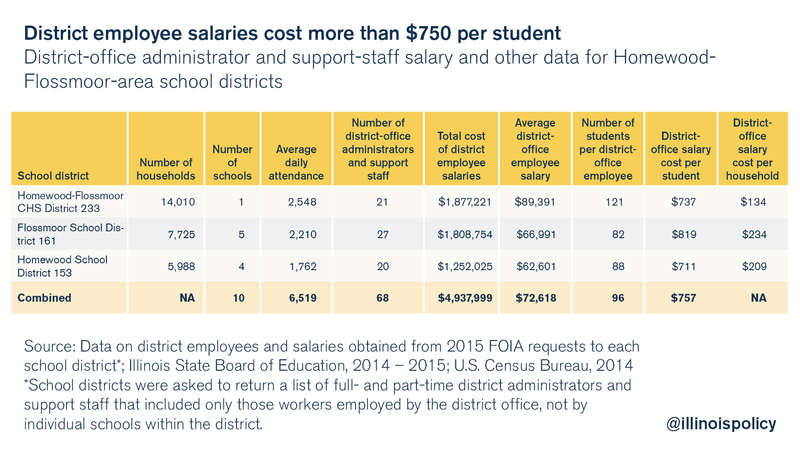

Another example is Homewood-Flossmoor Community High School District 233 and its two elementary feeder districts. Consolidation would cut down on the three districts’ 68 office administrators, saving local taxpayers over $5 million a year in salary costs, or over $750 per student.

Those savings don’t include the massive reduction in pension costs that would also occur through consolidation.

The consolidation solution

This report does not encourage school consolidation – the decision to consolidate schools should remain in the hands of local taxpayers. But these same local taxpayers shouldn’t be on the hook for multiple layers of government – in the form of school districts – that duplicate services, waste tax dollars, increase government debt, and decrease transparency.

Given the challenges facing consolidation efforts, district consolidation will only happen when the state partners with local districts to discuss concerns and craft a solution.

That partnership should come in the form of a district consolidation commission, which would work with local governments to create consolidation and reorganization guidelines, select candidate districts, and establish a process for implementation. The commission would also support the creation of legislation that would mandate its proposed recommendations through an up or down vote, meaning no amendments would be permitted, in the General Assembly.

However, the commission should also be relatively narrow in its scope of recommendations. School district consolidation should focus on reining in the duplicative costs of district administration only – not on equalizing salary contracts or funding new facilities. The state should not provide any incentives for those items, nor should it mandate any school consolidations. And to prevent local property taxes from rising, the commission should develop policies on limiting the merger of local bargaining units in newly combined districts.

If considered carefully and implemented properly, school district consolidation could provide serious financial benefits to both local taxpayers and the state, have a positive effect on student outcomes, and increase government transparency at the local level.

Illinois has too many school districts

From 1930 through 1970, a gradual consolidation process eliminated 9 of every 10 school districts nationally. The number of districts in the U.S. fell dramatically, to fewer than 20,000 from over 120,000.

Illinois followed similar trends. In 1942, Illinois had more than 12,000 districts – the most of any state in the nation. Over 10,000 of these were one-room schools with an average enrollment of 12 students. By 1955, the state had cut the number of districts to 2,242, and by the year 2000, the district count had fallen to 894.

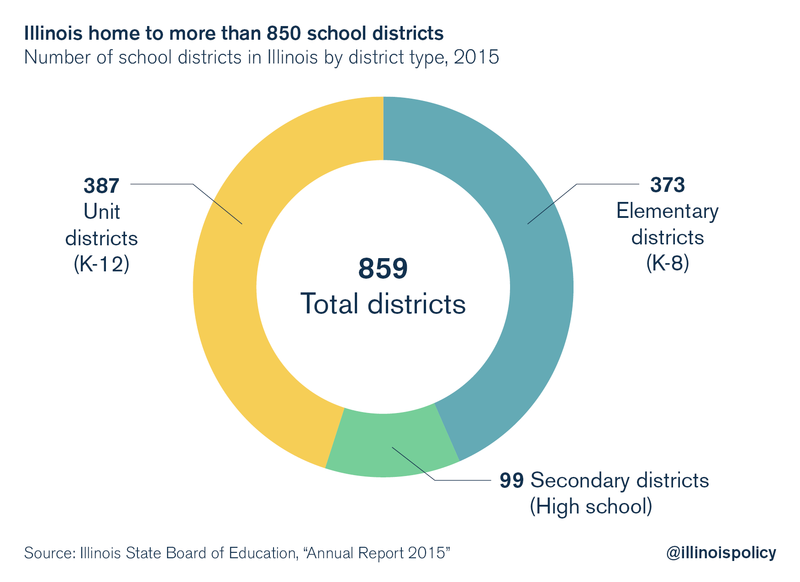

Today, Illinois has 859 school districts. Nearly 45 percent are elementary, 12 percent are secondary (high school), and 45 percent are unit districts, meaning they serve both elementary and secondary students.

Despite the massive reduction in Illinois school districts, the state is still not efficient when compared with its 14 peer states that also serve 1 million or more students. Florida, for example, averages 40,012 students per district. Georgia, North Carolina, California and Virginia all serve more than twice the 2,400 students per district Illinois does.

If Illinois school districts served the same number of students as school districts in California, the most populous state in the country, serve, Illinois would have just 342 school districts. And if Illinois school districts served the same number of students as North Carolina’s, Illinois would have just one-fifth of the school districts it has today – and one-fifth of the administrative bloat.

Too many small districts

Small student populations in many Illinois districts also contribute to the inefficiencies of Illinois education. Of Illinois’ 859 school districts, more than one-third serve fewer than 600 students. An additional layer of administration, over and above what already exists at the school level, is excessive and expensive for school districts of this size.

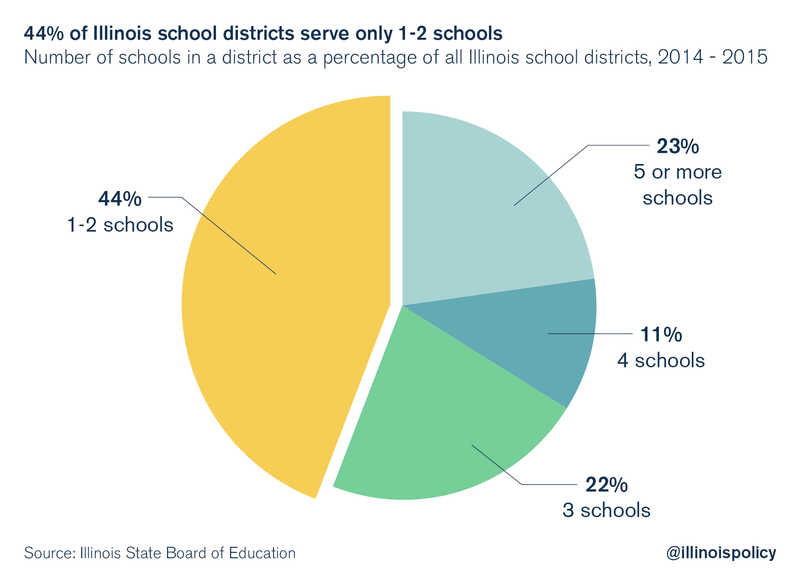

There are many school districts that oversee too few schools. Twenty-five percent of school districts in Illinois, or 212, are single-school districts.

Another 152 school district offices serve just two schools. This kind of mismanagement presents plenty of opportunities to merge district supervision and reduce administrative costs without interfering with the schools’ daily operations.

Merging elementary school districts with their high school districts

Finally, there exist many opportunities to consolidate high school districts with their elementary feeder districts. As many of these districts already share boundaries, students and a local tax base, consolidations can be less complex.

Illinois already has 387 such districts, called unit districts, which serve all elementary and secondary students in that district. However, the state still has 373 independent elementary school districts eligible for consolidation with the 99 independent high school districts they feed.

Moreover, Illinois is extremely inefficient in its student-to-district ratio. Over 60 percent of Illinois’ districts contain just 14 percent of Illinois’ students, based on average daily attendance. Those 511 districts serve on average only 526 students.

By contrast, the remaining districts average nearly 4,700 students (or 3,690 students if Chicago School District 299 is excluded from the calculation).

This inefficient distribution of students and resulting excess bureaucracy costs taxpayers a great deal of money. Not only do local taxpayers fund the principals, administrators, teachers and buildings at the school level, but they also pay for an additional – and often duplicative – layer of administration at the school district level.

The high cost of school district administrations

Salaries

District administrative staffs are costly for the taxpayers who pay for them. Six-figure salaries are common in school district administrations. In fact, 320 Illinois school district administrators, primarily district superintendents, make $200,000 or more in compensation annually.

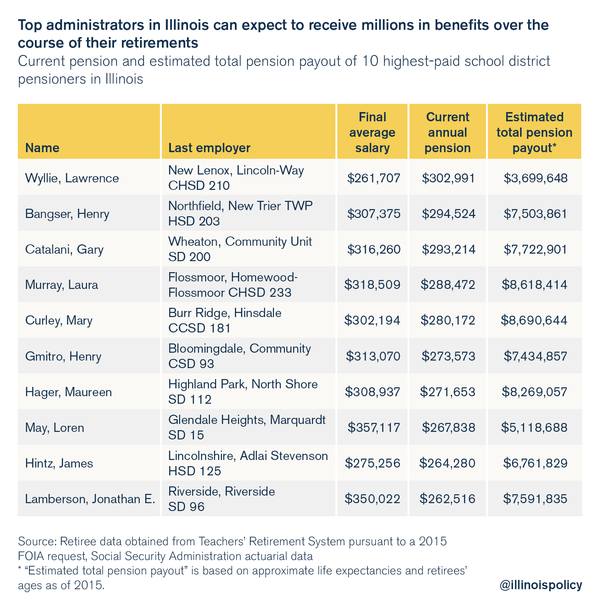

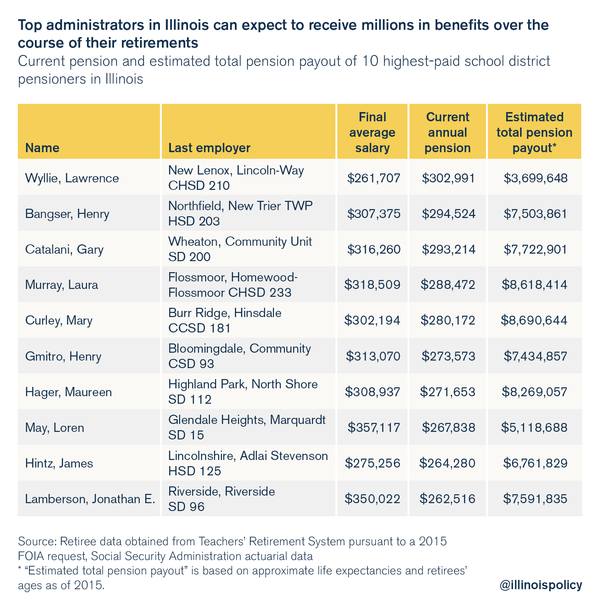

More than three-quarters of Illinois’ 872 superintendents have six-figure salaries, and many also get additional benefits in car and housing allowances, as well as bonuses. Their high salaries lead to generous future pension benefits: Superintendents on average receive $2 million to $6 million dollars in total pension benefits over the course of their retirements.

For example, the highest-paid superintendent in the state, Troy Paraday of Calumet City School District 155, received $400,449 in total compensation in 2015. Once he retires, Paraday can expect to receive more than $6 million to $8 million in benefits over the course of his retirement.

Paraday and other district superintendents are not the only well-paid administrators. Over 230 districts have assistant superintendents, and 9 out of 10 assistant superintendents make more than $100,000 annually.

But the full cost of each district’s administration encompasses far more than just top administrator salaries. It also includes the cost of other staff members.

District administrative staffs often include business services, human resources, facility and technology directors. The salaries of district staff add up, leading to another major cost – pensions.

Pensions

Duplicative district administrators directly increase costs for the state due in large part to the pension benefits these employees receive upon retirement.

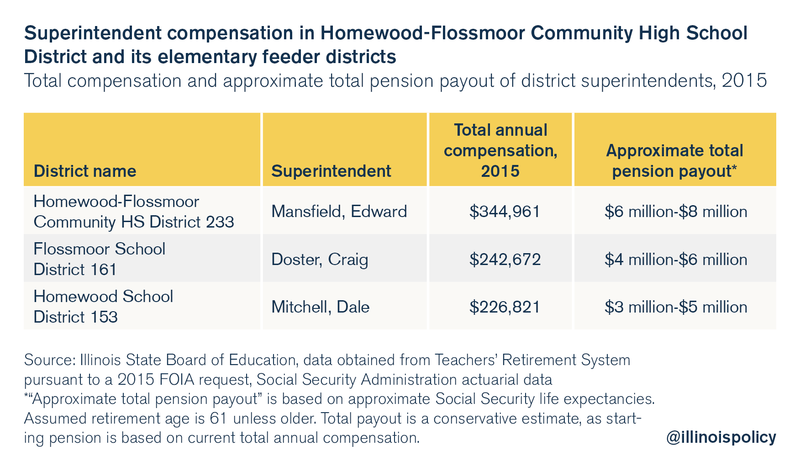

Most retired former superintendents are on track to receive millions in pension benefits over the course of their retirements. For example, consider Laura Murray, a former superintendent of Homewood-Flossmoor Community High School District 233 who retired in 2008 at the age of 58 and received a starting annual pension of $238,882.

Murray retired in her 50s and receives an automatic 3 percent increase to her annual pension every year after age 61. Assuming she lives to her approximate actuarial life expectancy, Murray can expect to receive more than $8 million in pension benefits over the course of her retirement.

High pension payouts, however, are not limited to superintendents. District staff with starting pensions of $75,000 can expect to earn pensions in excess of $2 million over the course of their retirements.

Without a serious reduction in the cost of pensions, the state will continue to divert funds away from students in classrooms to pay for teacher and administrator retirements. At the current rate of spending growth, state spending on educator retirements will outpace classroom spending by 2025.

Case studies: New Trier and Homewood-Flossmoor

New Trier Township

New Trier Township encompasses several wealthy communities on Chicago’s North Shore. The area has six elementary school districts that feed into a single high school district. A vast majority of funding for the districts (90 percent or more) is provided by local property taxes.

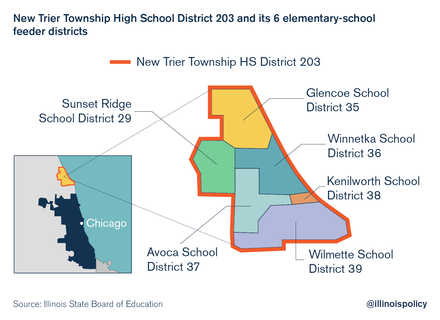

New Trier Township High School District 203 is coterminous (meaning it shares boundaries) with its six elementary districts, which include, for example, Kenilworth School District 38, whose only school serves just 488 students, Sunset Ridge School District 29, whose two schools serve 441 students, and Avoca School District 37, which has just two schools and 662 students.

Combined, the student population for the seven districts totals nearly 12,000.

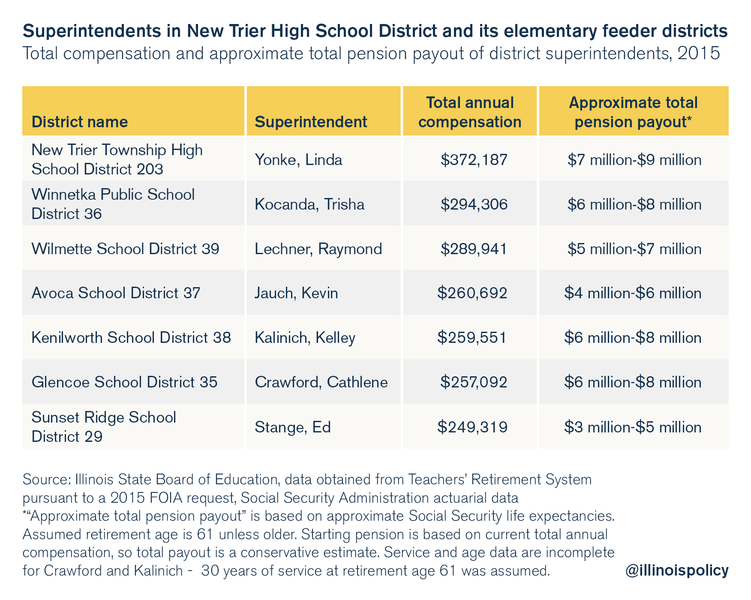

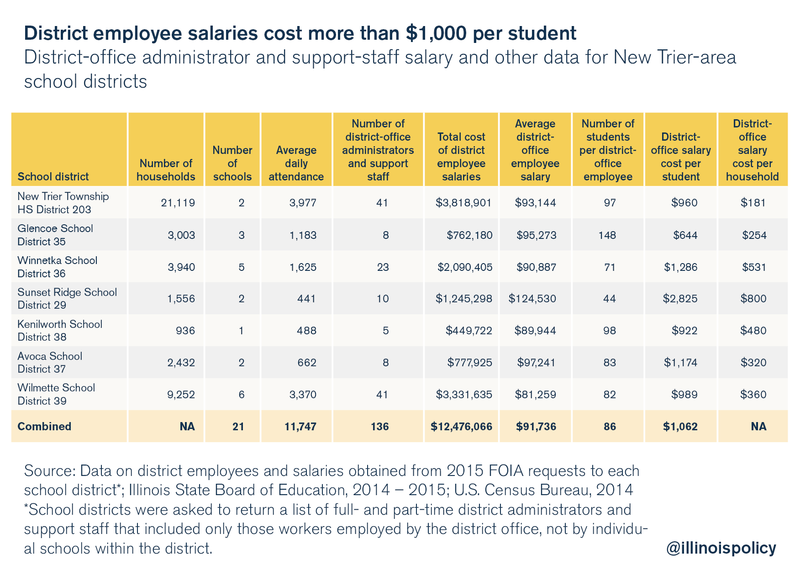

With six different K-8 school districts feeding into a single high school district, taxpayers are required to pay for seven different superintendents. The average total compensation for the superintendents in the seven districts is over $280,000 per superintendent. If the area’s elementary districts were combined with the high school district, New Trier could reduce the number of superintendents down to one, from the current seven. That would save local taxpayers millions of dollars a year, just from the reduction in superintendent compensation alone.

But reducing the number of duplicative superintendents is only a start. A majority of administrative staff in each district could be eliminated if the seven districts consolidated.

Wilmette School District 39, for example, employs 41 different administrative and support staff, including a technology director, computer technicians, a communications director, a business manager and curriculum and human resources directors – to name a few.

Many of those positions are duplicated across districts – which could be eliminated by consolidating. Instead of seven administrators handling communications, there would be only one, for example.

In all, the base salaries of all seven district staffs cost New Trier-area taxpayers over $12 million a year. That’s over $1,000 per student. By consolidating seven sets of staff into one, New Trier could save local taxpayers millions of dollars annually.

In addition, because the state pays the pension costs of K-12 educators to the Teachers’ Retirement System, taxpayers from Effingham to Carbondale to Quincy are chipping in for New Trier district staff and administrative pensions. By consolidating just their superintendents, New Trier could save state taxpayers $30 million over the next several decades.

And because the communities in the area are so similar – they already share a common tax base through the high school district, are relatively wealthy, and contain a similar amount of property wealth per student – the financial and tax logistics of integrating the communities into one overall school district would be relatively simple compared with more economically diverse areas.

Homewood-Flossmoor area

Homewood-Flossmoor encompasses several communities in Chicago’s Southland area – the villages of Homewood and Flossmoor and small parts of Glenwood, Hazel Crest and Chicago Heights. The area has two elementary school districts that feed into a single high school district. A majority of funding for the districts (70 percent or more) is provided by local property taxes.

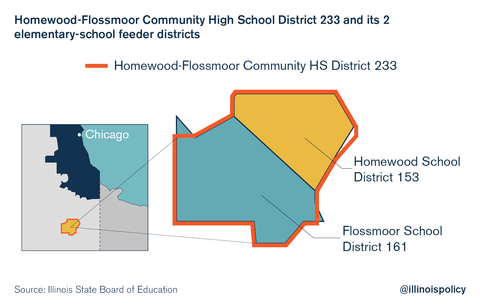

Homewood-Flossmoor Community High School District 233 shares boundaries with its two elementary districts: Flossmoor School District 161, which has five schools and serves 2,210 students, and Homewood School District 153, which has four schools and serves 1,762 students. Combined, the student population for the three districts totals more than 6,500.

With two K-8 school districts feeding into a single high school district, area taxpayers are required to pay for three different superintendents. The average compensation for the three superintendents is $270,000. If the area’s elementary districts were combined with the high school district, Homewood-Flossmoor could reduce the number of superintendents down to one and save local taxpayers half a million dollars a year, just from the reduction in superintendent compensation alone.

But reducing the number of duplicative superintendents is only a start. A majority of administrative staff in each district could be eliminated if the three districts consolidated.

Flossmoor School District 161’s district office, for example, employs 27 different people, from directors of curriculum and technology, to a health secretary and several bookkeepers.

Many of those positions are duplicated across the three districts – which could be eliminated through consolidation. Instead of three technology directors, there would be only one, for example.

In all, the base salaries of all three district staffs cost Homewood-Flossmoor-area taxpayers nearly $5 million a year. That’s over $750 per student. By consolidating three staffs into one, Homewood-Flossmoor could save local taxpayers millions of dollars annually.

In addition, because the state pays the pension costs of K-12 educators to the Teachers’ Retirement System, taxpayers from Effingham to Carbondale to Quincy are chipping in for Homewood and Flossmoor’s district staff and administrative pensions. By consolidating just their superintendents, the three districts could save state taxpayers $9 million over the next several decades.

And because the communities in the area are so similar – they already share a common tax base through the high school district, contain residents with relatively similar incomes, and contain a similar amount of property wealth per student – the financial and tax logistics of integrating the communities into one overall school district would be relatively simple compared with more economically diverse areas.

What the research says

The rationale for school district consolidation – improved efficiency and a reduction in massive overhead costs – is fairly straightforward. But consolidation, nationwide and in Illinois, has been hard to come by in recent years, triggering significant scholarly research on its benefits and costs.

When it comes to district size, research shows that efficiencies result when districts operate at some “sweet spot” regarding the number of total students in the district. And while not all studies show conclusive results, there is evidence that consolidation can modestly improve graduation rates and has a positive effects on student wages after graduation.

It’s important to make one critical distinction about consolidation research. While research is modestly positive regarding district consolidations, it is decidedly negative on school consolidations. Most research finds that for students, smaller schools are better than larger ones. Further, many of the costs found in district consolidation are really a function of subsequent school consolidations, which can lead to increased transportation costs, capital costs due to new facilities, less engagement by parents at the larger school, and diminished morale among the teaching staff.

There are other potential costs created by district consolidations. These occur when states provide transition funds to merging districts in the form of teacher salary equalizations, operating subsidies and new facility funding. Other potential costs to taxpayers can occur when consolidation affects property values and property taxes.

Following are three key studies conducted on the effects of school district consolidation:

Berry and West (2008)

After the thousands of school and district consolidations performed between the 1930s and the 1970s, little holistic research tested the claims that consolidations would lead to improved efficiencies and benefit students. Education progressives argued that school consolidations, particularly in rural areas, would solve the problems of a lack of qualified teachers, limited administrative expertise, and the need for greater course offerings.

Christopher Berry and Martin West, researchers from the University of Chicago and Harvard, respectively, set out to analyze the national, long-term data (1930 through 1970) of school and district consolidations in terms of student outcomes. Rather than look only at test scores, Berry and West chose to analyze real-life outcomes, such as earnings and educational attainment. They found that, after controlling for other factors, district consolidation led to lower high school dropout rates, higher college attendance and a 2 percent increase in earnings as district sizes increased by 1,000 students.

Yet their findings show that school consolidations, which had the opposite effect on earnings and education attainment, often served to wipe out the gains of district consolidation. States with smaller schools had greater educational attainment and lower dropout rates. This was particularly true for minority and low-income students.

The takeaway for Illinois is that district consolidations make sense, but significant school consolidations do not. The authors also caution that their findings focus on average school and district sizes, and they offer no view on optimal sizes.

Duncombe and Yinger (2005)

The Berry and West results analyzed the first wave of consolidations in the U.S. Further research by William Duncombe and John Yinger on New York’s rural district consolidation from 1987 to 1995 also finds benefits to consolidation, though they focus on identifying economies of size in operating and capital spending. The research shows that “doubling enrollment cuts total annual costs per pupil by 31 percent for a 300-pupil district and by 14 percent for a 1,500-pupil district.” The authors find that capital spending costs are also reduced, though less significantly. Critical to the findings, however, is the need to control capital projects and post-consolidation incentives, as they can serve to greatly diminish the benefits of district consolidation.

The authors conclude that there appear to be diminishing returns to the benefits of consolidation above a certain district size. While consolidating districts makes economic sense, creating mega-districts may lead to increased costs. The sweet spot for district size is in the 3,000-student range, according to Duncombe and Yinger. Other research suggests districts can successfully be as large as 6,000 students.

Hoxby (2000)

Caroline Hoxby of Harvard also points to potential diminishing returns of consolidation. Hoxby did not research consolidation per se, but the relationship between the number of school districts in metropolitan areas and its effect on school performance. She finds that competition among a larger number of districts and greater consumer choice from among the competing districts leads to higher student achievement and lower spending. Where enrollment is concentrated in a smaller number of districts, competition drops, and school productivity suffers.

Hoxby’s paper suggests a second sweet spot, not just in the size of individual districts, but also in the number of districts in a given region. Without sufficient district competition and choice for consumers of education, student outcomes are diminished. Hoxby’s findings suggest that district administrative consolidations should be used to maintain or increase the options available to families, not limit them.

Other states

From 2003 to 2004, Arkansas consolidated almost 20 percent of its smaller, rural districts in an attempt to create efficiencies and reduce the number of districts with fewer than 350 students. Importantly, the state did not mandate school consolidations in any way; the goal was to preserve small, high-performing schools that delivered quality. Arkansas found a way to “introduce administrative efficiencies without endangering the quality of the educational experience that can be realized in an intimate setting surrounded by a supportive community.”

Florida has taken school district consolidation to the maximum in terms of district size. Florida’s constitution calls for school districts based on county borders. While the average district has over 40,000 students, the state’s 67 districts vary significantly. The state’s 29 smallest districts have 1,000 to 10,000 students, while the seven largest districts have 100,000 to 400,000 students. Illinois only has one district that large – the Chicago Public School District.

Florida is also one of the leading states in educational reform and has generated some of the most improved educational outcomes in the nation, particularly with low-income and minority students. Relying on relatively large districts may not be the key factor in this success – Florida is also a lead innovator in school choice, accountability and online learning initiatives – but the existence of countywide districts certainly hasn’t compromised learning gains. Large districts have also benefited taxpayers, as Florida spends approximately $3,000 less per pupil than Illinois and has much smaller unfunded pension liabilities.

Nevertheless, Florida and six other states – Hawaii, Louisiana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico and Utah – have debated recent proposals to divide their mega-districts into smaller districts. This move suggests, in tandem with the research discussed above, that there is a sweet spot for the size and number of districts.

In summary, most research points to opportunities for Illinois to gain efficiencies from district consolidation, though it cautions against the creation of mega-districts. Additionally, the research strongly suggests that the state should not mandate any increase in school size. Evidence points to decreasing educational outcomes, in particular for lower-income students.

Consolidation roadblocks in Illinois and how to overcome them

The rules for passing a consolidation referendum are relatively straightforward. To consolidate two school districts, a petition must be signed by either the local school boards or by 50 registered voters or by 10 percent of the voters residing within each affected district. After a public hearing, both the regional and state superintendents must vote to approve the petition. Finally, the petition is presented as a referendum, which must pass by a majority of those voting in each affected district.

But it’s not the process that has held consolidation back. It’s the politics. Over the past 15 years, the number of districts in Illinois has fallen by just 35 districts, to 859 from 894.

While the financial benefits of school district consolidation are clear, consolidation efforts run into opposition from local taxpayers for a variety of reasons.

Many opponents of school district consolidations express concern over the loss of local control. They worry that schools will be closed and local communities will be hurt.

But taxpayers should not confuse school district consolidation with school consolidations. Any laws that consolidate school districts should remain neutral on school consolidations. School consolidations should remain local decisions to be decided by local boards of any newly unified school districts.

There is also concern about the potential costs created by district consolidations. These costs can occur when the state tries to do more than reduce the administrative excess at the district level. For example, in the past the state has provided transition funds to merging districts to equalize the terms in teacher contracts, subsidize operations, and fund new facilities.

In any future consolidations, the state should not provide any such incentives. The goal of school district consolidation is to rein in the duplicative costs of school district administrations – not facilitate school consolidations or equalize salary contracts.

Others also worry about the economics of merging with a nearby district. Merging diverse districts with different wealth, socioeconomic, and educational attainment is inherently complex. And where the consolidation of districts means drawing new boundaries, there will be highly politicized debates over control of valuable tax-generating property.

That means any plan for school district consolidations must include the heavy involvement of local communities in cooperation with state officials.

The path to consolidation

Given the challenges facing consolidation efforts, district consolidation will only happen when the state partners with local districts to discuss concerns and create a cooperative solution.

That partnership should come in the form of a district consolidation commission, which would function in a manner similar to the federal government’s Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission.

The district commission should set consolidation and reorganization guidelines, select candidate districts and establish a process for implementation, taking into account the concerns of local communities. The commission should further support the creation of legislation that would mandate its proposed recommendations through an up or down vote, meaning no amendments would be permitted, in the General Assembly.

However, the commission should also be relatively narrow in its scope of recommendations. School district consolidation should focus on reining in the duplicative costs of district administrations only – not on equalizing salary contracts or funding new facilities. The state should not provide any incentives for those items, nor should it mandate any school consolidations. And to prevent local property taxes from rising, the commission should develop policies on limiting the merger of local bargaining units in newly combined districts.

Conclusion

Rather than punish Illinois residents with more tax hikes, the state and local governments must pursue reforms including pension reform and school district consolidations. Local taxpayers shouldn’t be on the hook for multiple layers of government that duplicate services, waste taxpayers’ money, increase government debt, and decrease transparency.

The numbers speak for themselves: More than 60 percent of local property taxes in Illinois go toward school funding. And with the large number of districts in Illinois ripe for consolidation, the financial benefit cannot be ignored. A reduction of school districts by half could lead to operating savings of nearly $130 million to $170 million annually and could conservatively save the state $3 billion to $4 billion in pension costs over the next 30 years.

The state also has a stake in consolidating school districts. Illinois government is a large and sometimes the largest, provider of school funds for many Illinois school districts and is responsible for paying for school district pensions. By virtue of its responsibility to taxpayers, it has the duty to identify waste and propose efficiencies.

The benefits of consolidation would go beyond saving taxpayers money. District consolidation can have a positive effect on student outcomes and would increase transparency as well.

Considered carefully and implemented properly, school district consolidation can provide important benefits to Illinois taxpayers, local school districts and Illinois students.