Illinois has some of the most unfair laws in the region when it comes to negotiating with government worker unions. That, in turn, drives up the cost of operating government.

And that cost is passed on to taxpayers.

Illinoisans are suffering under one of the highest state and local tax burdens in the nation.1 Property taxes are particularly oppressive. Illinois homeowners pay some of the highest property tax rates in the U.S.2

It’s an unfair system in which exorbitant government spending is passed on to taxpayers, whose own incomes have remained stagnant.3

The people, in turn, are voting with their feet. Illinois’ migration losses are the worst in the region.4,5 And not surprisingly, taxes are the No. 1 reason people want to leave Illinois.6

The high cost of living in Illinois is driving people away.

One of the cost drivers: Illinois’ unfair collective bargaining laws.

Under Illinois law, government workers can organize and form unions for negotiating employment contracts and other purposes. This includes a variety of state and local workers, including teachers. “Collective bargaining” refers to the process of contract negotiations that occur between the government employer and the union representing the employees.

Government worker unions in Illinois can negotiate over just about anything – from wages to sick days to school start times.7 What’s more, there are no limits to the duration of the contracts negotiated. Contracts can lock taxpayers into paying for wage increases or bene ts for 10 years or more. All of that gets expensive.

Collective bargaining laws are complex. No two states regulate government employer-employee relations in the exact same way.

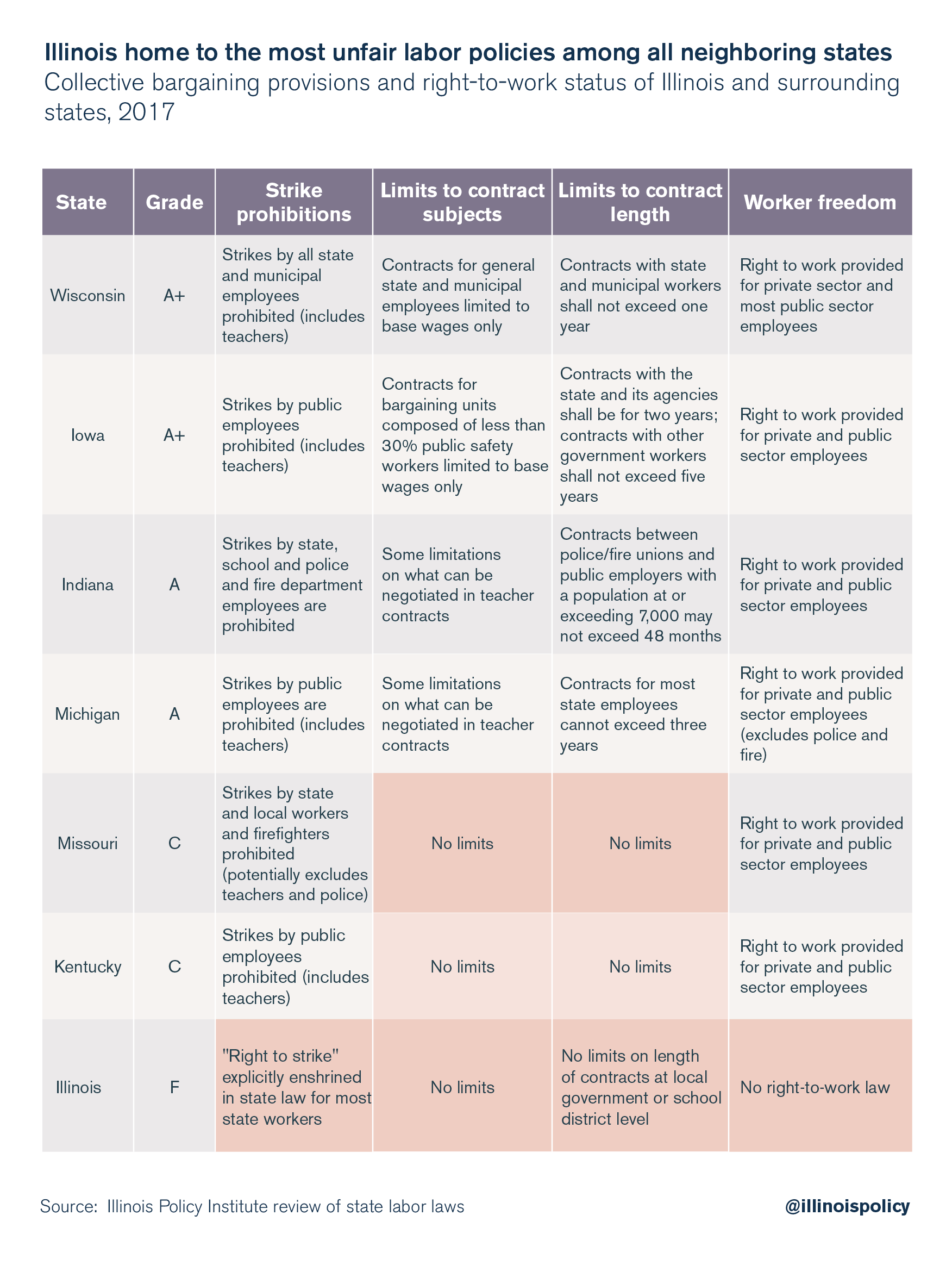

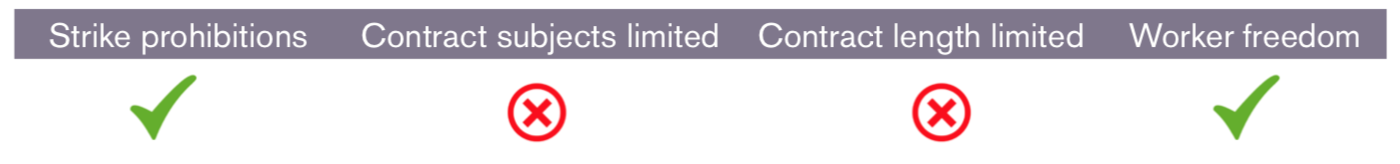

But a close examination of laws in each of Illinois’ neighboring states – Wisconsin, Iowa, Missouri, Kentucky, Indiana and Michigan – reveals a number of trends in the region. All six states have enacted two or more of the following provisions to help level the playing eld for taxpayers:

- Strike prohibitions for most or all government employees

- Limits on the subjects that can be negotiated during bargaining

- Limits on contract length

- Worker freedom provisions

In other words, every one of Illinois’ neighboring states has attempted to rein in government costs through collective bargaining provisions. Those states also provide more freedom to government workers by allowing them to choose whether to financially support a union.

Taking steps to reform collective bargaining laws is the norm in the states surrounding Illinois. Illinois, which has enacted none of the aforementioned provisions, is the outlier in the region.4

Each of the aforementioned provisions – strike prohibitions, limits to contract subjects, limits to contract length and worker freedom – is discussed in this report. A grade ranking – based on the extent to which Illinois and its neighbors have (or have not) enacted these provisions – is provided in the appendix, followed by detailed report cards.

If Illinois is going to compete with its neighbors – and keep people from moving out of the state – it must reduce the enormous property tax burden its families are forced to bear. Following the lead of surrounding states by enacting collective bargaining reforms is one good place to start.

Strike prohibitions

One of the most glaring differences between Illinois and its neighbors is that Illinois alone gives most government worker unions the power to strike.8 While every state surrounding Illinois prohibits strikes for most or all government workers, Illinois has gone in the opposite direction, enshrining a “right to strike” in state law.9

A government worker strike is different than a strike in the private sector. When government worker unions threaten to strike, they are threatening to shut down government functions and deprive residents of necessary services. It isn’t the party sitting on the other side of the negotiating table, such as the governor or a school board, that directly bears the harm – it is the residents themselves.

The power to strike is not merely theoretical. It plays out across the state regularly:

- In May 2017, faculty at the University of Illinois-Spring eld walked out on students just one week before finals.10

- In February 2017, Illinois’ largest government worker union – representing 35,000 state workers across Illinois – authorized a strike if Gov. Bruce Rauner attempted to implement a contract the union didn’t like.11

- In September 2016, teachers in Champaign voted in favor of a strike after students were already in school for the year.12

- Since 2012, the Chicago Teachers Union has gone on strike or threatened to go on strike at least four times.13

That potential assault on the people by unionized public employees contributed to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s belief that unions have no place in the public sector:

“Particularly, I want to emphasize my conviction that militant tactics have no place in the functions of any organization of Government employees. … Since their own services have to do with the functioning of the Government, a strike of public employees manifests nothing less than an intent on their part to prevent or obstruct the operations of Government until their demands are satisfied. Such action, looking toward the paralysis of Government by those who have sworn to support it, is unthinkable and intolerable.”14

Yet under Illinois law, strikes by government workers aren’t just tolerated – they’re expressly permitted by state law.

The power to strike gives unions the upper hand in negotiations, and that drives up costs.15

For example, when CTU went on strike in 2012, Chicago Public Schools was already facing a $1 billion budget deficit and an $8 billion teacher pension shortfall.16 But CTU went on strike anyway, demanding higher wages even though CTU members already received high salaries and generous bene ts. In fact, Chicago teachers are some of the highest-paid among the nation’s 50 largest school districts.17

After the strike ended, CPS announced it had to close 50 schools and lay off thousands of teachers to help reduce costs.18 That eventually led to property tax hikes to fund schools.

And look at the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. In the midst of Illinois’ fiscal crisis, AFSCME is adamant that the state spend an additional $3 billion in increased wages and benefits – including wage increases up to 29 percent over the course of the contract.19 It isn’t enough that state workers in Illinois are already the highest-paid state workers in the nation when adjusted for the cost of living.20 Union leaders want more, and they are willing to go on strike – and risk the well-being of Illinoisans – to have those demands met.

Conversely, every one of Illinois’ neighbors prohibits most or all government workers from going on strike.

Prohibiting government worker strikes helps even the playing eld. And it helps ensure a state’s residents can get the services they need, without interference by government worker unions.

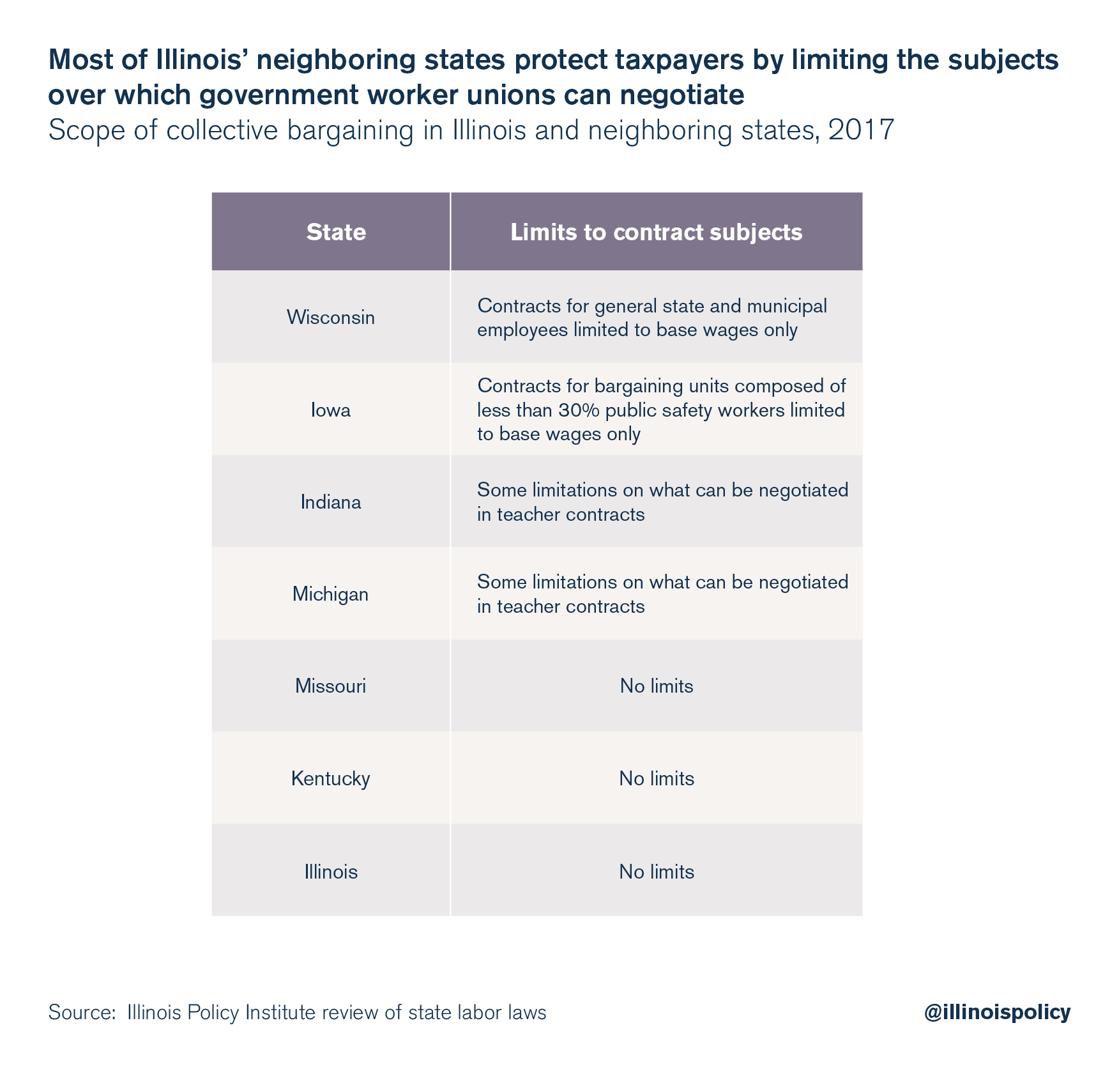

Limits on contract subjects negotiated

In Illinois, virtually all subject matter related to a government worker’s employment is open to negotiation. Specifically, state law provides that negotiations between a government unit and a government worker union include “wages, hours, and other conditions of employment.”21

That’s virtually an unlimited range of negotiable subjects – including provisions as minute as school calendars or start times. And that drives up costs by inhibiting government flexibility.

Take, for example, East Aurora School District 131. In April 2017, the school board approved a plan that would provide first-ever bus transportation to 3,000 students in the district.22 With almost three-quarters of district students categorized as low-income, it was a move that could help raise attendance, test scores and the graduation rate.23

To make the transportation plan more economically feasible (and, therefore, more taxpayer-friendly), the school district considered staggering start times at the schools.24 That would mean the same buses could make multiple runs – and the district could pay for fewer buses. According to the district, staggering start times would lower its three-year busing costs by more than $343,000.25

But day-to-day logistics – such as when the school day starts and when students can arrive at the school – are covered by the district’s contract with the teachers union. That meant school start times could not be altered without union consent. And union of officials indicated that could mean an additional year of planning before they would agree to the busing proposal, if at all.26

To provide transportation for the 2017-2018 school year, the school district moved forward by providing additional buses, but did not stagger start times – costing taxpayers more.27

If it weren’t so costly, the plethora of subjects Illinois government worker unions negotiate would be laughable. Take, for example, the contract between the city of Kankakee and the Office and Professional Employees International Union. In addition to holidays and vacation, municipal workers covered by the contract are guaranteed an extra day off each year – for their birthdays.28

What’s more, the broad array of subjects negotiated into contracts bogs down the process and undermines the “labor peace” Illinois’ collective bargaining laws were supposed to support in the first place. From the city level to the county level to the state level,29 in Illinois it can take months or even years of negotiations to iron out all the details involved in the multitude of subjects. The most obvious example: The 35,000 state employees represented by AFSCME have been without a contract for over two years.30

Failing to negotiate contracts in a timely manner creates an uncertain work environment for affected employees – not to mention inflated costs of retaining labor lawyers or other consultants for extended periods of time.

But four of Illinois’ neighbors have limited the subjects over which government worker unions can negotiate: Wisconsin, Iowa, Indiana and Michigan.

Wisconsin and Iowa limit collective bargaining to base wages only for general state and local government worker unions. Other topics – such as overtime, holiday pay and vacation time – cannot be negotiated.

Indiana and Michigan prohibit only some subjects from negotiations – such as school calendars or teacher merit pay.

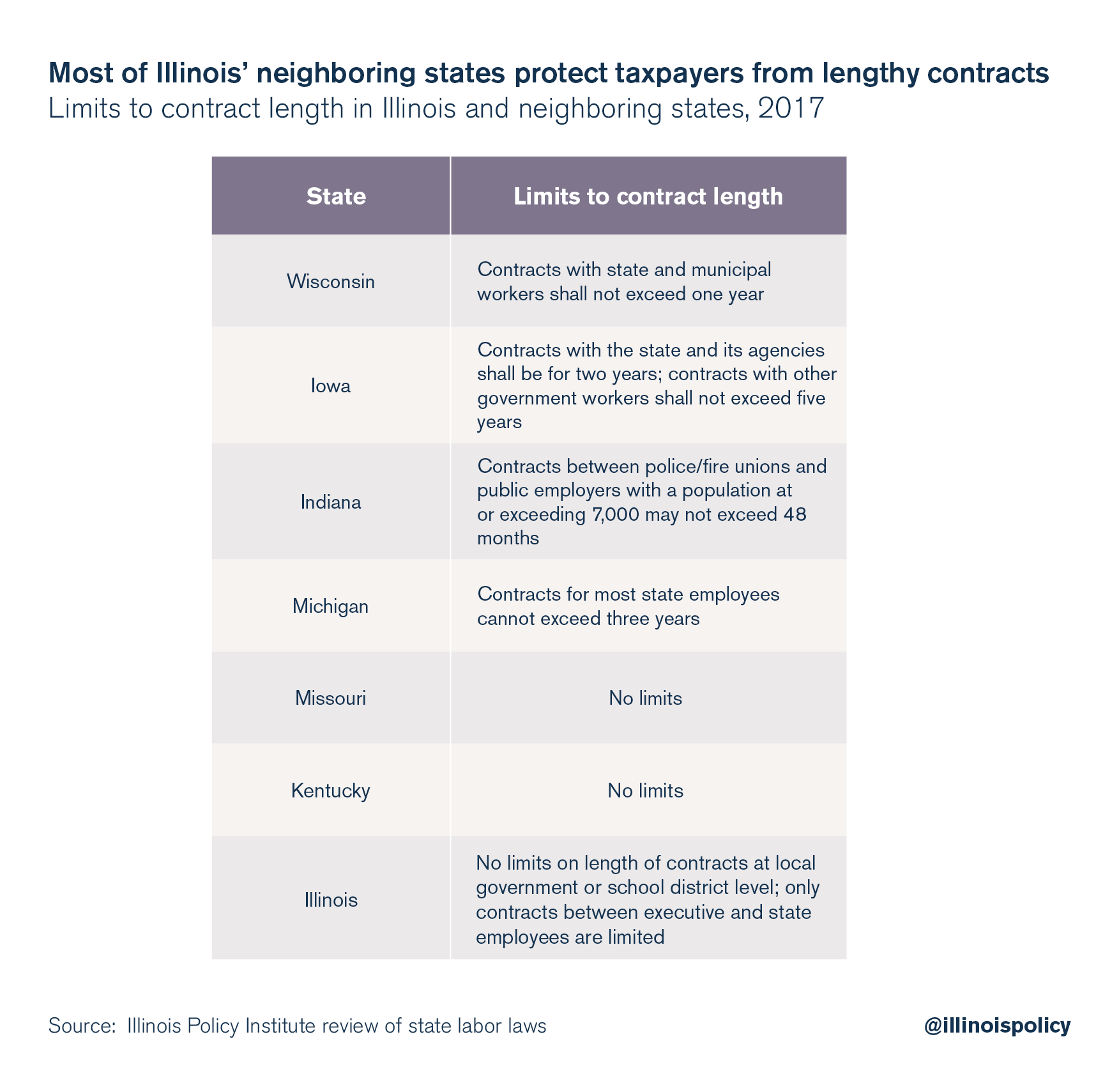

Limits on contract duration

Under Illinois law, there is no limit on the length of most government worker contracts. Lengthy collective bargaining agreements can leave taxpayers on the hook for expensive contract provisions many years into the future – even if the state or local economy can no longer support the provisions.

With income growth stagnant, the last thing Illinoisans need is to be locked into paying for contracts that promise salaries and bene ts they can’t afford, far into the future. And that sort of arrangement isn’t speculative in Illinois.

Just look at what happened in Palatine-area Community Consolidated School District 15. In 2016, school district officials signed an unprecedented 10-year contract with the Classroom Teachers’ Council, the union representing District 15’s teachers.31 Under that contract, taxpayers, who already face stagnant earnings and decreased purchasing power, will be contractually bound to provide increasing salaries even if – four or more years down the line – the economy cannot sustain such increases.32

In addition to in inflating costs, lengthy contracts inhibit the ability of Illinoisans to hold their elected leaders accountable. For example, if Palatine-area residents don’t like the teacher contract, they can vote in new school board leaders at the next election. But with a 10-year contract on the books, the impact of voting in new members won’t be felt for a long time. In 10 years, a school board could turn over multiple times before new members would ever have the chance to negotiate a new contract.

On the other hand, four of Illinois’ neighbors restrict the length of collective bargaining agreements: Wisconsin, Iowa, Indiana and Michigan.

In other words, some or all government worker contracts in those states cannot surpass a specified amount of time.

In other words, some or all government worker contracts in those states cannot surpass a specified amount of time.

Worker freedom provisions

The majority of U.S. states – 28 in total – are right-to-work states.33

Right-to-work laws allow workers to opt out of union membership and out of financially supporting the union. A worker cannot lose his job because he doesn’t want to pay fees to a union he does not support.

In Illinois, government workers who wish to opt out of union membership have only two options. If they object to union membership on the basis of religious belief, they can opt out of membership. But such workers are still required to pay fees – equal to the amount of union membership fees – to a nonreligious charitable organization.34

The only other option is to become a fair share payer. As fair share payers, workers still pay fees – up to 100 percent of the amount of union dues – to the union.35 These fees are supposed to represent the worker’s “fair share” of what it costs the union to represent workers in negotiating with the state.

But that means fair share payers are still forced to pay money to a union they may not even support. And that’s a violation of the employees’ First Amendment freedoms of association and speech.

While Illinois has taken no steps to provide worker freedom to government employees, all six of Illinois’ neighbors have passed right-to-work laws.

Conclusion

Illinois’ failure to enact provisions that ease the pressure placed on taxpayers by the state’s collective bargaining laws make it an outlier in the region.

Internal Revenue Service data show Illinois is already suffering a net loss of people and income to all of its neighboring states.36 And according to polling by the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute, the No. 1 reason Illinoisans want to leave the state is high taxes.

If Illinois is going to compete with its neighbors – and make the state a more attractive place to live and work – it must reduce the enormous property tax burden its families are forced to shoulder. Illinois can take an important step toward that goal by following the lead of neighboring states in enacting commonsense collective bargaining reforms.

All the states surrounding Illinois protect the First Amendment rights of workers through worker freedom provisions. Those states have also enacted laws that help rein in government worker union costs and power – including strike prohibitions, limits on what can be negotiated into government worker contracts and limits on the duration of those contracts. Illinois stands alone in doing nothing. For the sake of its residents and the state’s economic viability, that needs to change.

Appendix: State report cards

Each report card includes specific details regarding the states’ laws in the following areas:

- Strike prohibitions for most or all public employees

- Limits on the subjects that can be negotiated during bargaining

- Limits on contract length

- Worker freedom

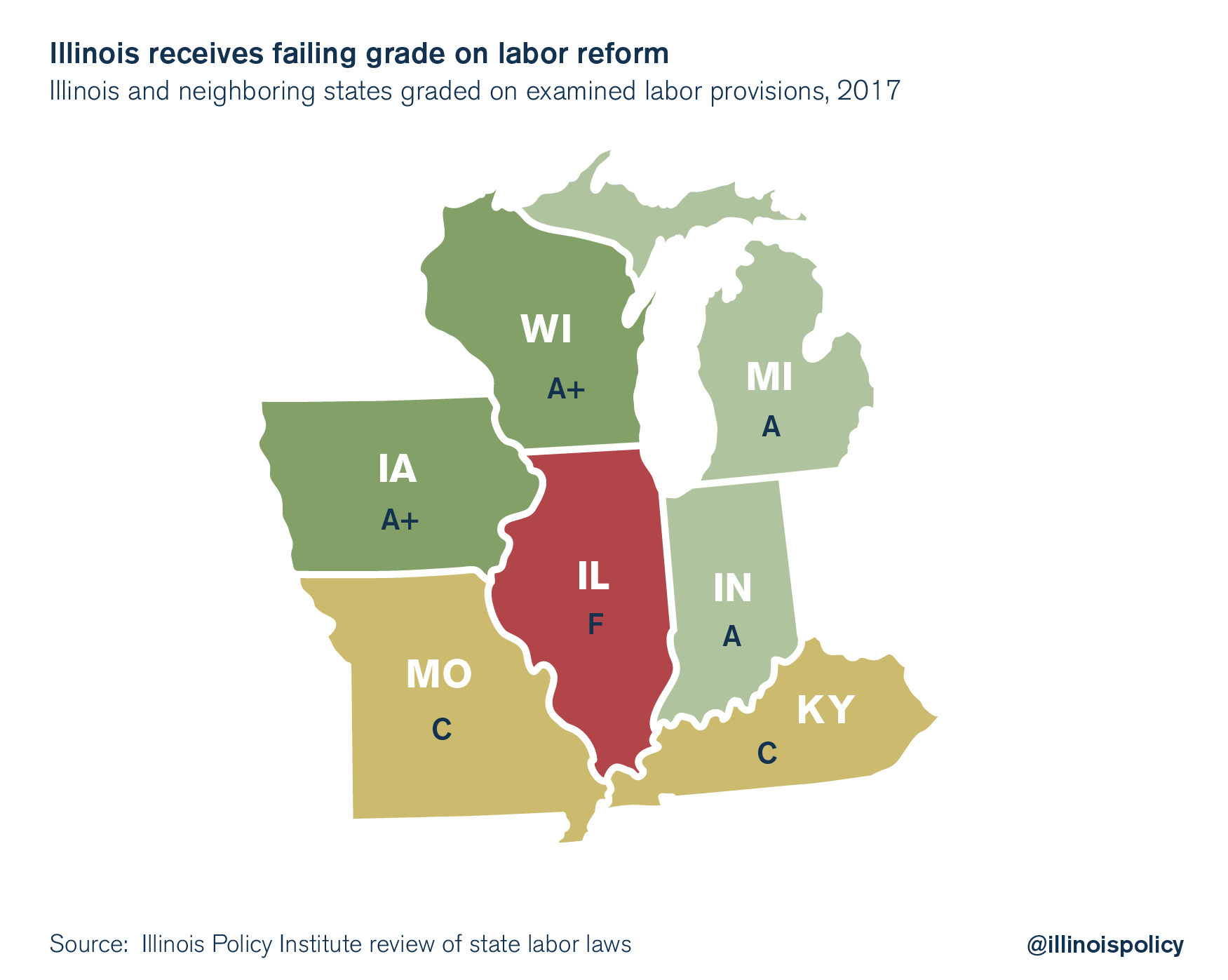

Illinois and its neighbors earned grades based on the following metrics37:

- A+ – These states have enacted all four of the examined provisions, including limiting negotiations to bargaining over base wages only. Wisconsin and Iowa fall into this category.

- A – These states have enacted all four of the examined provisions, but only prohibit some subjects from being negotiated at the bargaining table. Indiana and Michigan fall into this category.

- B – These states have enacted three of the examined provisions. None of Illinois’ neighboring states fall into this category.

- C – These states have enacted two of the examined provisions. Missouri and Kentucky fall into this category.

- D – These states have enacted one of the examined provisions. None of Illinois’ neighboring states fall into this category.

- F – These states have enacted no significant labor reforms. Illinois is the only state to fall into this category.

A sampling of other collective bargaining reforms is also listed in the report cards. While not included in the rubric for grading the states, these provisions further demonstrate the states’ commitment to leveling the playing field between taxpayers and unions representing government workers.

Wisconsin – Grade: A+

Wisconsin ushered in a new era of collective bargaining reform in 2011 when it passed Act 10, which included provisions limiting the subjects of negotiations to base wages only. The state’s collective bargaining laws now include every one of the provisions examined, earning it an A+ in the state rankings.

Strike prohibitions

- Strikes by state employees are prohibited. It is an unfair labor practice for a state employee to engage in, induce or encourage any employees to engage in a strike.38

- Strikes by municipal employees are “expressly prohibited.”39 This includes any employee of a city, county, town, village, school district or any other political subdivision of the state.40

Contract subjects limited

- Collective bargaining for general state employees is limited to base wages only.41 This limitation does not apply to public safety employees.42

- Collective bargaining for “general municipal employees” is limited to base wages only.43 “General municipal employees” does not include public safety employees or transit employees.44

- In both instances, “base wages” excludes overtime, premium pay, merit pay, performance pay, supplemental compensation, pay schedules and automatic pay progressions.45 Like other subjects, those are prohibited from negotiations.

Contract duration limited

- No agreements with a union representing general state employees may be for a period that exceeds one year. Agreements cannot be extended.46

- Except for the initial collective bargaining agreement between a municipal employer and a union representing “general municipal employees,” every contract shall be for a term of one year and may not be extended.47

- Initial collective bargaining agreements for transit employees cannot be longer than three years. Subsequent agreements cannot be longer than two years.48

Worker freedom

- Right to work is available for private sector employees and general (i.e., nonpublic safety) public sector employees.49

Unique provisions

- In addition to limiting negotiations to base pay, any base wage increases for either general state employees or general municipal employees are limited to increases in the consumer price index.50

- A wage increase for general state employees that exceeds increases in the consumer price index requires a statewide referendum.51

- A wage increase for general municipal employees that exceeds increases in the consumer price index requires: 1) a resolution by the local government unit and 2) a referendum approving the resolution.52

- A wage increase for school employees that exceeds increases in the consumer price index requires: 1) a resolution by the school board and 2) a referendum approving the resolution.53

- Unions representing general municipal employees or general state employees must be certified as the unit’s representative annually.54 This allows workers regular opportunities to vote on which union represents them – or whether to have a union at all.

Iowa – Grade: A+

Iowa could be considered “Wisconsin 2.0” in terms of labor reforms. In 2017, the Iowa Legislature passed House File 291, which, among other reforms, limited the subjects of collective bargaining as well as the duration of government worker contracts.55 With Wisconsin, Iowa is paving a reform path for other states to follow.

Strike prohibitions

- The public policy of the state is to “prohibit and prevent all strikes by public employees.”56 Public employees include any workers employed by the state, its boards, commissions, agencies, departments and political subdivisions – including school districts.57

- It is unlawful for any public employee or union to induce, instigate, encourage, authorize, ratify or participate in a strike against a public employer.58

Contract subjects limited

- All retirement systems, dues check-offs and other payroll deductions for political action committees or other political contributions are excluded from the scope of negotiations.59

Further restrictions are determined by the percentage of employees in a bargaining unit who are public safety employees.60 - Bargaining units composed of less than 30 percent public safety employees can negotiate for base wages only.61 Insurance, leaves of absence for political activities, supplemental pay, transfer procedures, evaluation procedures, procedures for staff reduction and subcontracting public services are explicitly excluded from negotiations.62

- Bargaining units composed of at least 30 percent public safety employees can negotiate wages, hours, vacations, insurance, holidays and other terms of employment.63

Contract duration limited

- Collective bargaining agreements with the state and its agencies “shall be for two years.”64

- Collective bargaining agreements for other government workers “shall not exceed ve years.”65

Worker freedom

- Right to work is available for private sector employees and public sector employees.66

Unique provisions

- If a government worker union goes on strike and is held in contempt of court for failure to comply with an injunction, the union shall be immediately decertified and cannot be certified again as the employees’ representative until after 24 months have elapsed.67

- Recertification of a government worker union must occur before expiration of the union’s collective bargaining unit68 – i.e., at least every two to ve years, per contract duration limits.

- The initial bargaining session – when the government worker union presents its initial bargaining position to the employer – is open to the public. Likewise, the second bargaining session – when the public employer presents its initial bargaining position – is also open to the public.69

Indiana – Grade: A

Indiana stands apart in completely prohibiting collective bargaining for state employees.70 But that is not the case for local government employees or teachers. For that reason, provisions are necessary to protect taxpayers from collective bargaining pitfalls. Indiana has enacted several provisions, earning the state an A.

Strike prohibitions

- Strikes by state employees are illegal, including strikes by state police.71

- Strikes by school employees are unlawful.72

- Strikes by police or re department employees are prohibited.73

Contract subjects limited

- Indiana places some limitations on what can be negotiated in teacher contracts, specifically excluding subjects such as the school calendar, teacher dismissal procedures and criteria, and the formula for supplemental pay for certain teachers with advanced degrees.74

- Similarly, stipends to individual teachers in a particular year are not subject to collective bargaining.75

- Police and re employers must discuss issues and proposals related to wages, hours of employment and other conditions and terms of employment, but they are only required to “meet and confer.”76

Contract duration limited

- Agreements between police or firefighter unions and public employers with a population at or exceeding 7,000 may not exceed 48 months.77

Worker freedom

- Right to work is available for private sector employees and public sector employees.78

Unique provisions

- Any police or firefighter union that engages in a strike loses the right to represent the employees for at least 10 years.79

A police or re employer cannot enter into an agreement that will place the employer in a position of deficit financing.80 - It is unlawful for a school employer to enter into any agreement that would place the employer in a position of de cit spending. Such a contract is void to that extent.81

- A decision whether to grant a charter school is not subject to restraint by a collective bargaining agreement.82

Michigan – Grade: A

Like Wisconsin, Michigan enacted significant labor reforms in 2011 and 2012, including right to work.83 Other provisions – such as prohibiting government worker strikes and limiting contract duration for most state employees – earn it a solid A in the regional state rankings.

Strike prohibitions

- Strikes by public employees are prohibited.84 A “public employee” is defined to include anyone holding a position in state government or a political subdivision of the state, in public school service, or “in any other branch of public service.”85

Contract subjects limited

- Michigan places some limitations on what can be negotiated with teachers unions, including the following prohibited subjects: teacher evaluations, merit pay, layoffs/recalls, number of school days, tenure, use of volunteers at schools, whether an authorizing body can grant a contract and operate a school academy, and whether to contract for noninstructional support.86

Contract duration limited

- Collective bargaining agreements for most state employees cannot exceed three years.87

Worker freedom

- Right to work is available for private sector employees and public sector employees.88 Police and re department employees and state police troopers and sergeants are excluded.89

Unique provisions

- Michigan law allows an “emergency manager” – a person appointed by the governor to a municipality or school district experiencing a financial emergency90 – to meet and confer with a union. If, in his sole discretion and judgment, a prompt and satisfactory resolution is unlikely to be obtained, he has the authority to reject, modify or terminate one or more terms of a collective bargaining agreement.91

Missouri – Grade: C

Missouri has been on a multiyear path toward collective bargaining reform. In 2015, the state’s legislature enacted right-to-work provisions, but the law was vetoed by then-Gov. Jay Nixon, a Democrat.92 With Nixon term-limited, the people of Missouri elected Republican candidate Eric Greitens in 2016. Greitens fulfilled one of his campaign promises by signing newly enacted right-to-work legislation in 2017, making Missouri the 28th right-to-work state.93

Strike prohibitions

- Missouri law prohibits strikes by state and local workers and firefighters.94

- There is no law regarding strikes by police or public teachers.95

Contract subjects limited

- Missouri does not limit the subjects that can be negotiated.

Contract duration limited

- Missouri does not limit the length of government worker contracts.

Worker freedom

- In 2017, Missouri enacted a law making right to work available for private sector employees and public sector employees.96 The law is currently on hold for private sector employees after opponents of worker freedom delivered petitions calling for a public vote.97

Kentucky – Grade: C

Like Missouri, Kentucky’s path to reform has been years in the making. A Democrat-controlled House of Representatives had prevented right to work from becoming a reality in the state, but the 2016 election saw that chamber return to the Republicans for the first time since 1921.98 In early January 2017, Gov. Matt Bevin signed right-to-work legislation into law – making it the 27th right-to-work state in the nation.99 The law ensures that workers do not have to pay union fees just to keep their jobs.

Strike prohibitions

- No public employee may engage in a strike or work stoppage.100 A “public employee” is any person working for a “public agency,” which includes state and local government units and school districts.101

- Strikes by firefighters and other public safety workers are also explicitly prohibited.102

Contract subjects limited

- Kentucky does not limit the subjects that can be negotiated.

Contract duration limited

- Kentucky does not limit the length of government worker contracts.

Worker freedom

- Right to work is available for private sector employees and public sector employees.103

Illinois – Grade: F

Illinois’ failure to enact any reasonable collective bargaining reforms has made it an outlier in the region. As a result, government units cannot function in the most efficient and economic manner possible. That artificially inflates the cost of running government by billions of dollars each year104 – slamming residents who are barely getting by with higher and higher taxes.

Strike prohibitions

- A “right to strike” is explicitly guaranteed for most government sector workers.105 That means government workers can walk out on the taxpayers they are supposed to be serving – threatening to shut down government programs and services people need.

- Only “security employees of a public employer, Peace Officer units, or units of firefighters or paramedics” are prevented from going on strike.106

Contract subjects limited

- Illinois does not limit the subjects that can be negotiated.

Contract duration limited

- Illinois law provides that a collective bargaining agreement between a state agency or department and the union representing its employees may not extend beyond June 30 of the year in which the governor and other executive branch officers begin their terms.107 That provides an effective limit on the length of contracts with state employees.

- But Illinois does not limit the length of government worker contracts at any other level, including local government units and school districts.

Worker freedom

- Illinois does not maintain right-to-work provisions for workers in either the private or public sectors.

Endnotes

- Brendan Bakala, “Illinois Has Highest Overall Tax Burden in the Nation,” Illinois Policy Institute, March 15, 2017.

- Austin Berg, “Illinois Property Taxes Highest in the U.S., Double the National Average,” Illinois Policy Institute, April 28, 2016. In fact, Illinois has higher effective property tax rates than the nine states that don’t have an income tax. Michael Lucci, “Illinois Has Higher Property Taxes than Every State with No Income Tax,” Illinois Policy Institute, February 14, 2017.

- Illinois’ personal income growth during the first quarter of 2017 was a mere 0.6 percent. With inflation running at nearly 0.5 percent per quarter, Illinoisans experienced virtually no real income growth. See Michael Lucci, “Income Report Shows Illinois Staggering Along with Nation’s Worst Income Growth,” Illinois Policy Institute, July 10, 2017.

- Michael Lucci, “Illinois’ 2015-2016 Out-migration Problem Is Much More Dire than in Other Midwestern States,” Illinois Policy Institute, January 11, 2017.

- Given the state’s oppressive tax burden, it’s no surprise that Illinoisans’ No. 1 reason for wanting to leave the state is taxes. Paul Simon Public Policy Institute poll, Illinois Voters Ask: Should I Stay Or Should I Go?, October 10, 2016.

- Paul Simon Public Policy Institute poll, Illinois Voters Ask: Should I Stay or Should I Go?.

- In Illinois, state and local government worker unions are governed by the Illinois Public Labor Relations Act, 5 Ill. Comp. Stat. 315/1 et seq.; teachers unions are governed by the Illinois Educational Labor Relations Act, 115 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/1 et seq. See also Mailee Smith, “5 Examples of Government Union Power over the People, and 2 Solutions to Fix the Problem,” Illinois Policy Institute, 2017.

- The only exclusion under Illinois’ laws is certain public safety workers. See 5 Ill. Comp. Stat. 315/14. See also Mailee Smith, “Stacked Deck: Of All Neighboring States, Only Illinois Gives Strike Powers to Government Unions,” Illinois Policy Institute, August 31, 2017.

- See, e.g., Illinois Public Labor Relations Act, 5 Ill. Comp. Stat. 315/17.

- Staff report, “A Week Before Final Exams, UIS Professors Go On Strike,” Springfield State Journal-Register, May 1, 2017.

- Mailee Smith, “Illinois State Workers Authorize Strike,” Illinois Policy Institute, February 23, 2017.

- Nicole Lafond, “Updated: Champaign Teachers Give OK to Strike,” Champaign News-Gazette, September 7, 2016.

- Mailee Smith, “Noble Teachers Beware: Unionizing Invites CTU Involvement in Your School,” Illinois Policy Institute, April 18, 2017.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Letter on the Resolution of Federation of Federal Employees Against Strikes in Federal Service” (August 16, 1937).

- Mailee Smith, “AFSCME: The 800-Pound Gorilla at the Negotiating Table,” Illinois Policy Institute, 2016.

- John Klingner, “3 Reasons Why Chicagoans Can’t Afford the Latest CTU Contract,” Illinois Policy Institute, October 11, 2016.

- Amy Korte, “Chicago Teachers Highest Paid Among Nation’s 50 Largest School Districts,” Illinois Policy Institute, February 5, 2016.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, “6 Reasons the Chicago Teachers Union Has No Business Striking Again,” Illinois Policy Institute, November 30, 2015.

- Mailee Smith, “AFSCME’s List of Demands,” Illinois Policy Institute, January 24, 2017; Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, “AFSCME’s Contract Demands: A Close Look at the $3B Hit to Taxpayers,” Illinois Policy Institute, February 8, 2017.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, “Illinois State Workers Highest Paid in Nation,” Illinois Policy Institute, Spring 2016.

- See Illinois Public Labor Relations Act, 5 Ill. Comp. Stat. 315/1 et seq.; Illinois Educational Labor Relations Act, 115 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/1 et seq.

- Sarah Freishtat, “In Historic Vote, East Aurora Adds Everyday Busing for Schools,” Aurora Beacon-News, April 18, 2017.

- See Illinois Report Card, “Aurora East USD 131: Low income students,” 2017; Freishtat, “Historic Vote.”

- Smith, “5 Examples of Government Union Power.”

- Sarah Freishtat, “East Aurora Union Chief: Slow Down on School Busing,” Aurora Beacon-News, May 3, 2017.

- Freishtat, “East Aurora Union Chief.”

- Mailee Smith, “School Buses Finally Arrive for East Aurora Students, But Unfairness Remains,” Illinois Policy Institute, September 1, 2017.

- Contract between the city of Kankakee and the Office and Professional Employees International Union (May 1, 2015 – April 30, 2018), obtained by Illinois Policy Institute via a Freedom of Information Act request.

- Mailee Smith, “Languishing Contract Negotiations Show Need for Labor Law Reforms in Illinois,” Illinois Policy Institute, September 22, 2017.

- Mailee Smith, “More than 2 Years Later, AFSCME Still Fighting State on New Contract,” Illinois Policy Institute, August 11, 2017.

- Mailee Smith, “Palatine-Area District 15’s New 10-Year Contract ‘Unprecedented,’” Illinois Policy Institute, April 25, 2016.

- Mailee Smith, “Palatine-Area District 15’s New 10-Year Contract.”

- National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, “Right to Work States,” 2017.

- 5 Ill. Comp. Stat. 315/6(g); 115 ILCS 5/11.

- 5 Ill. Comp. Stat. 315/6(e); 115 ILCS 5/11.

- Austin Berg, “IRS Data: Illinois Lost People and Income to Every Neighboring State on Net,” Illinois Policy Institute, December 4, 2017.

- Other recent rankings may differ slightly, but those rankings were created before Kentucky and Missouri enacted worker freedom provisions and before Iowa enacted its landmark 2017 collective bargaining reforms. See, e.g., Geoffrey Lawrence, James Sherk, Kevin Dayaratna and Cameron Belt, How Government Unions Affect State and Local Finances: An Empirical 50-State Review, (Heritage Foundation, April 11, 2016); Priya Abraham, Transforming Labor: A Comprehensive, Nationwide Comparison and Grading of Public Sector Labor Laws, (Commonwealth Foundation, November 13, 2016).

- Wis. Stat. § 111.84(2)(e). State employment relations are governed by Wis. Stat. §§ 111.81 et seq.

- Wis. Stat. § 111.70(4)(L).

- Wis. Stat. § 111.70(1)(i); Wis. Stat. § 111.70(1)(j). Employment relations between municipal employers and municipal employees are governed by Wis. Stat. §§ 111.70 et seq.

- Wis. Stat. § 111.91(3); see also Wis. Stat. § 825(5).

- Wis. Stat. § 111.91(3) specifically refers to “general employee[s].” See also Wis. Stat. §§ 111.91(1) and 111.91(2), which specifically apply to bargaining units under Wis. Stat. § 111.825(1) (i.e., public safety employees).

- Wis. Stat. § 111.70(4)(mb)(1).

- See Wis. Stat. § 111.70(4)(mc); Wis. Stat. § 111.70(1)(fm).

- Wis. Stat. § 111.70(4)(mb)(1); Wis. Stat. § 111.91(3)(a).

- Wis. Stat. § 111.92(3)(b). Each agreement must coincide with the fiscal year. Ibid.

- Wis. Stat. § 111.70(4)(cm)(8m).

- Wis. Stat. § 111.70(4)(cg)(8m).

- See Wis. Stat. § 111.04(3) (covering private sector employees); Wis. Stat. § 111.70(2) (covering general municipal employees); Wis. Stat. § 111.82 (covering general state employees). A referendum process for the institution of fair share fees for municipal and state public safety is outlined in state law. See Wis. Stat. § 111.70(2); Wis. Stat. § 111.85(1).

- Wis. Stat. § 111.91(3); Wis. Stat. § 111.70(4)(mb)(2).

- Wis. Stat. § 111.91(3)(b).

- Wis. Stat. § 66.0506(2).

- Wis. Stat. § 118.245(1).

- Wis. Stat. § 111.70(4)(d)(3)(b) (governing general municipal employees); Wis. Stat. § 111.83(3)(b) (governing general state employees).

- Portions of Iowa’s new provisions are in litigation, but none have been invalidated as of December 1, 2017.

- Iowa Code § 20.1(1).

- Iowa Code § 20.3(9); Iowa Code §20.3(10). Employment relations with public employees are governed by the Public Employment Relations Act, Iowa Code §§ 20.2 et seq.

- Iowa Code § 20.12(1).

- Iowa Code § 20.9(3).

- See Iowa Code § 20.9(1).

- Iowa Code § 20.9(1).

- Iowa Code § 20.9(3).

- Iowa Code § 20.9(1).

- Iowa Code § 20.15(6).

- Iowa Code § 20.9(4).

- See Iowa Code § 731.4; Iowa Code § 20.8.

- Iowa Code § 20.12(5).

- Iowa Code § 20.15(2)(a).

- Iowa Code § 20.17(3).

- See Ind. Code § 4-15-17-5.

- Ind. Code § 4-15-17-4; Ind. Code § 4-15-17-8; Ind. Code. § 4-15-17-1(b).

- Ind. Code § 20-29-9-1.

- Ind. Code § 36-8-22-15.

- Ind. Code § 20-29-6-4.5; Ind. Code § 20-28-9-1.5.

- Ind. Code § 20-43-10-3(g)(2).

- Ind. Code § 36-8-22-12(b); see also Ind. Code § 36-8-22-11(5).

- Ind. Code § 36-8-22-16; Ind. Code § 36-8-22-7(q).

- See Ind Code § 22-6-6-8; Ind. Code § 20-29-4-2; Ind. Code § 36-8-22-8.

- Ind. Code § 36-8-22-15(d).

- Ind. Code § 36-8-22-14.

- Ind. Code. § 20-29-6-3.

- Ind. Code § 20-24-6-8.

- F. Vincent Vernuccio, Top Labor Reforms for Michigan, (Mackinac Center for Public Policy, 2016).

- Mich. Comp. Laws § 423.202. See also Mich. Civil Service Commission Rules 6-12.4 and 6-15.

- Mich. Comp. Laws § 423.201.

- Mich. Comp. Laws § 423.215(3); Mich. Comp. Laws § 380.1249.

- Mich. Civil Service Commission Rule 6-3.8(b). Chapter 6 of the Michigan Civil Service Commission Rules governs employee-employer relations for the state’s civil service employees. “Civil service employees” are defined by Article XI, Section 5 of the Constitution of Michigan as “all positions in the state service except those filled by popular election, heads of principal departments, members of boards and commissions, the principal executive of cer of boards and commissions heading principal departments, employees of courts of record, employees of the legislature, employees of the state institutions of higher education, all persons in the armed forces of the state, eight exempt positions in the of ce of the governor, and within each principal department, when requested by the department head, two other exempt positions, one of which shall be policy-making.”

- Mich. Comp. Laws § 423.14(1); Mich. Comp. Laws § 423.209(2); Mich. Comp. Laws § 423.210(3).

- Mich. Comp. Laws § 423.210(4). A public employer and union may agree that the excluded employees “shall share fairly in the financial support of the labor organization.” Ibid.

- Mich. Comp. Laws § 141.1542(e); Mich. Comp. Laws § 141.1549(1).

- Mich. Comp. Laws § 141.1552(1)(k). The law provides guidelines for when this can occur – including a requirement that the contract provisions altered must be directly related to and designed to address the financial emergency.

- Jason Hancock, “Missouri House Fails to Override Governor’s Veto of ‘Right-to-Work’ Bill,” Kansas City Star, September 16, 2015.

- Jason Hancock, “Gov. Eric Greitens Signs Missouri Right-to-Work Bill, But Unions File Referendum to Overturn It,” Kansas City Star, February 6, 2017.

- Mo. Rev. Stat. § 105.530.

- The right to bargain was extended to police and teachers via a Missouri Supreme Court decision. The statute section prohibiting strikes by public employees does not specifically cover them. As such, police and teachers seem to be in a state of legal limbo when it comes to strikes. Cf. Lawrence, Sherk, Dayaratna and Belt, How Government Unions Affect State and Local Finances (reporting there is no law on police or teacher strikes), with Milla Sanes and John Schmitt, Regulation of Public Sector Collective Bargaining in the States (Center for Economic and Policy Research, March 2014) (stating that strikes are illegal for police and teachers).

- Mo. Rev. Stat. § 290.590.

- Summer Ballentine, “New Missouri Right-to-Work Law Suspended,” Springfield News-Leader, August 18, 2017.

- Tom Loftus, “GOP Takes Ky House in Historic Shift,” Louisville Courier-Journal, November 8, 2016.

- National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, “Right to Work States.”

- Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 336.130(1).

- Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 336.180; Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 61.870(1). On prohibitions of teacher strikes, see also Board of Trustees v. Public Employees Council No. 51 American Federation of States, 571 S.W.2d 616 (Ky. 1978); Jefferson County Teachers Assoc. v. Board of Education, 463 S.W.2d 627 (Ky. 1970).

- Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 345.130 (prohibiting strikes by firefighters); Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 67A.6910 (prohibiting strikes by police officers, firefighter personnel, firefighters and correction officers in urban-county governments); Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 67C.418 (prohibiting strikes by police officers of consolidated local governments); Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 70.262(1) (prohibiting strikes by deputies); Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 78.470 (prohibiting strikes by county employees in the classified service as police).

- 103 Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 336.130(3).

- Lawrence, Sherk, Dayaratna and Belt, How Government Unions Affect State and Local Finances.

- 5 Ill. Comp. Stat. 315/17.

- 5 Ill. Comp. Stat. 315/14.

- 5 Ill. Comp. Stat. 315/21.5(2). See also American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, Council 31 v. Illinois Labor Relations Board, 2017 IL App (5th) 160229 (Ill. App. Ct. Nov. 6, 2017).